Timers, Finalizers and Memory Leaks

I was involved in a production incident investigation recently related to a high memory usage by one of our .NET services. A process was gradually consuming more and more memory and eventually fails with OutOfMemoryException.

The memory dump contained quite a few large instances of the DataRefresher class:

public class DataRefresher : IDisposable

{

private readonly CancellationTokenSource _cts = new();

private readonly Task _refreshTask;

// The content that is periodically refreshed.

private byte[] _data;

public DataRefresher()

{

_refreshTask = Task.Run(RefreshToken);

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize();

}

~DataRefresher()

{

Console.WriteLine("~DataRefresher");

Dispose(false);

}

private async Task RefreshToken()

{

while (!_cts.Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

Console.WriteLine("Refreshing the data...");

// Actual code that refreshes the _data field.

await Task.Delay(1000);

}

}

private void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

_cts.Cancel();

if (disposing)

_cts.Dispose();

}

}

The class is disposable, and the Dispose method stops the while loop responsible for refreshing the data. If the user forgets to call Dispose, the class also has the finalizer to stop the refresh cycle, preventing memory leaks.

No memory leaks are possible, right? Not quite!

Here is the simplest way to see what will happen to an instance that is created and instantly abandoned:

var refresher = new DataRefresher();

var o = new object();

var wr1 = new WeakReference(o);

var wr2 = new WeakReference(refresher);

Thread.Sleep(1000);

GC.KeepAlive(refresher);

// Forcing the full GC cycle!

GC.Collect();

GC.WaitForPendingFinalizers();

GC.Collect();

Console.WriteLine($"object is alive: {wr1.IsAlive}");

Console.WriteLine($"refresher is alive: {wr2.IsAlive}");

The output is:

Refreshing the data...

object is alive: False

refresher is alive: True

To repro this locally, you need to run the code in Release mode and disable tiered compilation if running in .net6+ by setting this in the csproj file: <TieredCompilation>false</TieredCompilation>.

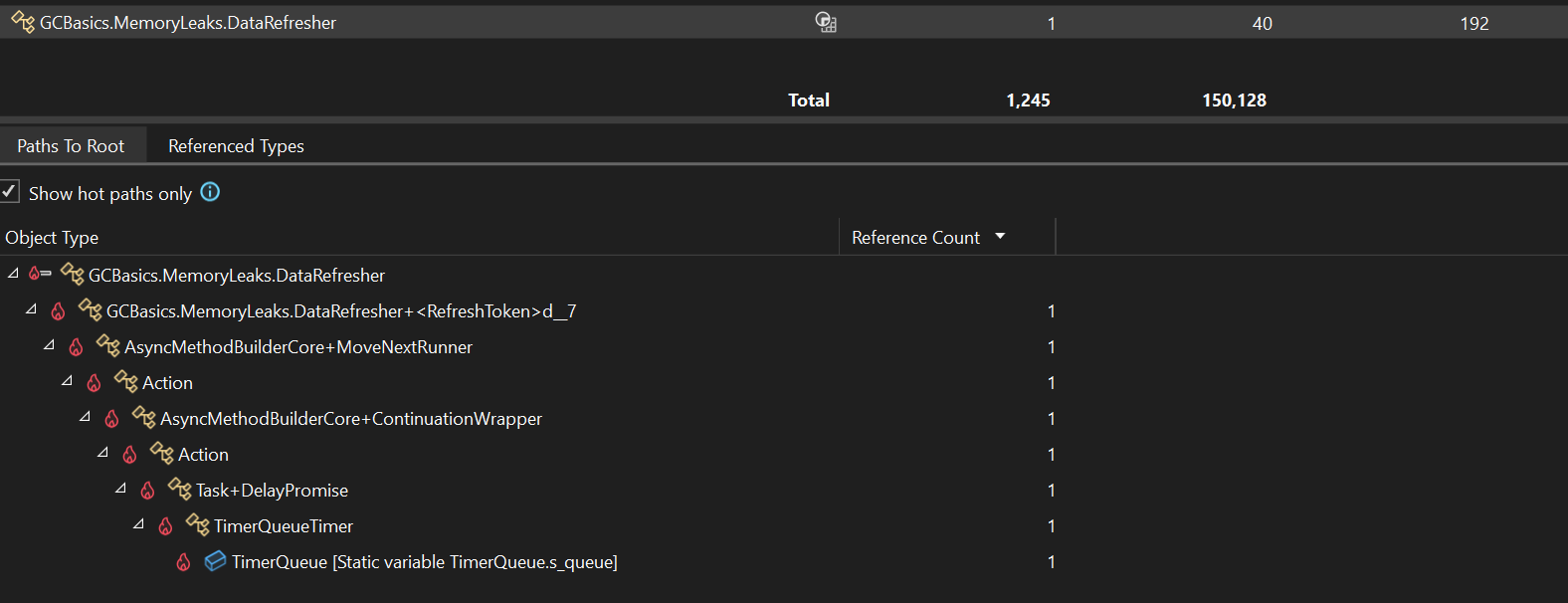

The output shows, that the refresher instance is alive, even though the instance created later was GC-ed ( * ). And we can attach the debugger and see in VS who references the instance:

( * ) When dealing with something non-obvious like GC behavior, always double-check the correctness of the experiment. I’ve intentionally added another instance (object o) to make sure a non-rooted object is collected by the GC. The GC is quite tricky and has a bunch of optimizations like GCInfo, responsible for tracking the lifetime of local variables. Such optimizations might be on or off depending on the context. For instance, GCInfo is off in debug mode and in Tier0 compilation. Try your best to avoid drawing the wrong conclusions based on flawed experiments..

The image shows the dependency path from the instance to an application root. We can see that the

The image shows the dependency path from the instance to an application root. We can see that the DataRefresher instance is eventually referenced by DelayPromise, which is backed by the timer queue. Since the timer is still running, the instance is still reachable, and because it is reachable, the finalization cannot stop the timer, leading to a chicken-and-egg situation where our ‘safety net’ (the finalizer) doesn’t work.

How to fix the issue?

Finalizers are designed to clean up unmanaged resources, but they can be useful in other cases too. When a Task or Task<T> fails and the user doesn’t observe the result, the finalizer raises a TaskScheduler.TaskUnobservedException event. We can apply the same principle here to ensure the ‘refresher’ doesn’t cause a memory leak if it is not properly disposed. ( * * ), ( * * * ).

( * * ) Are we responsible for making sure that the class is used correctly? In managed environment failure to call Dispose method could cause all sorts of issues, like race conditions, unauthorized access exceptions etc. But typically, not disposing a thing doesn’t cause a memory leak, since eventually the finalizer will clean-up the underlying unmanaged resource. If DataRefresher is used by multiple people and/or by multiple teams, I do think having such safety net is a good option.

( * * * ) Should we enforce the disposal via analyzers? I’ve found such analyzers way too verbose and I personally think they cause more harm then good.

We could split DataRefresher in 3 types:

DataRefresher- a facade with the same API as before. This class won’t have any functionality but will have two fields -DataRefresherImplandLifetimeTracker.DataRefresherImpl- a class with the timer and the old logic- and

LifetimeTracker- a finalizable instance that will notifyDataRefrehserfrom its finalizer that its no longer reachable.

This is a bit too complicated and not very reusable. Instead, we can have an async-friendly timer that will hold a weak reference to the DataRefresher.

public interface ITimerHandler

{

Task OnTimerElapsed();

}

public sealed class WeakTimer<T> where T : class, ITimerHandler, IDisposable

{

private readonly CancellationTokenSource _cts = new();

private readonly Task _refreshTask;

private readonly WeakReference<T> _target;

public WeakTimer(T target, TimeSpan duration)

{

_target = new WeakReference<T>(target);

_refreshTask = Task.Run(async () =>

{

while (!_cts.Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

if (_target.TryGetTarget(out var t))

{

// Probably worth having 'try/catch' around the user's code

await t.OnTimerElapsed();

// If the token is canceled due to a race condition, _refreshTask

// will fail, but it's ok.

await Task.Delay(duration, _cts.Token);

}

else

{

// The target is no longer alive! Stopping the timer!

Console.WriteLine("Stopping the timer, since the target was GCed!");

_cts.Cancel();

}

}

});

}

public void Dispose()

{

_cts.Cancel();

_cts.Dispose();

}

}

public class DataRefresher : IDisposable, ITimerHandler

{

private readonly WeakTimer<DataRefresher> _timer;

private byte[]? _data;

public DataRefresher()

{

_timer = new WeakTimer<DataRefresher>(this, TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1));

}

public void Dispose()

{

_timer.Dispose();

}

public Task OnTimerElapsed()

{

Console.WriteLine("Refreshing the data...");

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

Now we can run the same test as before to see that DataRefresher will be GC-ed:

Refreshing the data...

object is alive: False

refresher is alive: False

Stopping the timer, since the target was GCed!

Since WeakTimer<T> holds a weak reference, it makes DataRefresher to be eligible by the GC.

Conclusion

The GC is amazing, but its not magic. You could have memory leaks in managed environment and timers are notoriously famous for causing them. Having a simple building blocks like WeakTimer<T> will help avoiding memory leaks and might make the code a more reliable since “regular” timers could easily be mis-used in modern code and accidentally cause crashes for another reason. But this is story for another time…

Stay tune and be curious!