Classes vs. Structs. How not to teach about performance!

It’s been a while since my last blog post, but I believe it’s better to post late than never, so here I am!

Recently, I was browsing a list of courses on Pluralsight and noticed one with a very promising title: “C# 10 Performance Playbook.” As an advanced course on a topic I’m passionate about, I decided to give it a go. I wasn’t sure if I’d find many new things, but since I talk about performance a lot, I’m always looking for an interesting perspective on how to explain this topic to others. The content of this course raised my eyebrows way too much, so I decided to share my perspective on it and use it as a learning opportunity.

This blog post is quite similar to what Nick Chapsas does in his “Code Cop,” with one difference: I’m not going to anonymize the sample code. Since it’s paid content, I feel that I have a right to give a proper review and potentially ask for changes, since the potential damage of such content on a platform like Pluralsight could be quite high.

In this blog post, I want to focus on a single topic that was covered in a section called “Classes, Structs, and Records.” The section is just over six minutes long, and I didn’t expect too many details, since the topic is quite large. But you can be concise and correct.

Classes vs. Structs

Here is the first benchmark used for comparing classes vs. structs:

public class ClassvsStruct

{

// This reads all the names from the resource file.

public List<string> Names => new Loops().Names;

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandClasses()

{

var classes = Names.Select(x => new PersonClass { Name = x });

}

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandStructs()

{

var classes = Names.Select(x => new PersonStruct { Name = x });

}

}

The results were:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Rank |

|---------------- |---------:|---------:|---------:|-----:|

| ThousandStructs | 32.05 us | 0.639 us | 1.136 us | 1 |

| ThousandClasses | 34.11 us | 0.841 us | 2.480 us | 2 |

The author concluded that structs are slightly faster, which is an interesting conclusion given the fact that there were no constructions of classes or structs involved in the code. The difference between the two benchmarks is probably just noise and has nothing to do with the actual performance characteristics of classes or structs.

But that’s not all. Here is the next iteration of the benchmarks:

public class ClassvsStruct

{

// This reads all the names from the resource file.

public List<string> Names => new Loops().Names;

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandClasses()

{

var classes = Names.Select(x => new PersonClass { Name = x });

for (var i = 0; i < classes.Count(); i++)

{

var x = classes.ElementAt(i).Name;

}

}

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandStructs()

{

var classes = Names.Select(x => new PersonStruct { Name = x });

for (var i = 0; i < classes.Count(); i++)

{

var x = classes.ElementAt(i).Name;

}

}

}

The results are:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Rank |

|---------------- |---------:|----------:|----------:|-----:|

| ThousandStructs | 2.315 ms | 0.0460 ms | 0.0716 ms | 1 |

| ThousandClasses | 9.664 ms | 0.1837 ms | 0.3710 ms | 2 |

And I’m quoting the author: “This time the difference is HUGE!” My first reaction was, “Okay, he’s going to fix this, right? He’s just playing with us, expecting us to catch the issue in the code. You can’t have O(N^2) in the benchmark!” But nope, this was the final version of the code.

Even though I think this is a very bad way to compare structs and classes, let’s use this example to learn how we should be analyzing the results of the benchmarks.

Tip #1: Do not trust results you don’t understand

One thing every performance engineer should learn is the ability to interpret and explain the results. For instance, in this case, we changed the benchmarks to consume classes variable in a loop 1k times, and all of a sudden, the benchmark duration increased by 100x. Is it possible that accessing 1K elements in C# takes milliseconds? This sounds horrible! My gut reaction is that the construction is probably more expensive than the consumption, so I would not expect the benchmark to be significantly slower if done correctly. If you see a 100x difference in performance results, you should stop and think: why am I getting these results? Can I explain them? Is it possible that something is wrong with the benchmark?

Tip #2: Understand the code behind the scenes

In many cases, developers can rely on good abstractions and ignore the implementation details, but this is not true for performance analysis. In order to properly interpret the results, a performance engineer should be able to look through the abstractions and see what’s going on under the hood:

- What does the

Namesproperty do? What’s the complexity of accessing it? Is it backed by a field, or do we do some work every time we access it? - What’s the nature of the “collection” we use? Is it a contiguous block of memory? Is it a node-based data structure like a linked list? Is it a generated sequence?

- Do you understand how LINQ works? What’s the asymptotic complexity of the code?

All of these questions are crucial, since each and every step might drastically affect the results.

If the Names property is expensive, then the benchmark will be measuring the work it does instead of the code inside the benchmark. And in the author’s case it was reading a list of names from the resource file. Meaning that we were doing a file IO in a benchmark which is not ok.

Different collection types have different performance characteristics. Even though the O-complexity is still the same, you’ll see significant difference between accessing an array or a linked list. Probably, the differences should be insignificant in real world cases, but the benchmark should show it since accessing an array is more cache-friendly since all the data are co-located (especially for structs).

And once you arrive with a hypothesis, you can check it by writing a benchmark that just access the elements of an array vs. elements of linked list with 1K elements:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Rank |

|------------------------- |-----------:|----------:|----------:|-----:|

| StructAccessInArray | 639.7 ns | 23.60 ns | 67.32 ns | 1 |

| ClassAccessInArray | 776.9 ns | 39.18 ns | 111.14 ns | 2 |

| StructAccessInLinkedList | 4,526.5 ns | 114.47 ns | 332.11 ns | 3 |

| ClassAccessInLinkedList | 4,806.1 ns | 141.65 ns | 410.96 ns | 4 |

These are the results I would expect: less then a nano second for accessing an array, 20-ish % difference between classes and structs and a significant differences between accessing an array vs. accessing a linked list. But even in this case we should not draw any conclusions on how changing array to linked list would affect performance in a real-world cases, since the code normally does way more than just getting the data.

Lastly, it’s important for every .NET engineer to have a solid understanding of algorithmic complexity and how LINQ works. We’ll revisit this topic after the tips, as it’s a key issue with these benchmarks.

Tip #3: Understand the Concepts Being Measured

The final tip is: make sure you understand the concepts being measured. There are many differences between structs and classes, and your mental model of these constructs should match the results. For example, you know that classes are heap-allocated, while structs can be allocated on the stack or inside other objects, which can impact performance. Classes are references, while structs are values, which can also affect performance in various ways.

However, you should ask yourself if you can interpret the results with your knowledge and intuition. If the answer is “no,” it could be due to a lack of understanding of the concept in this context, a flawed benchmark that introduces noise, or other factors that affect the results that you still don’t understand. In any case, you should not draw any conclusions from data that you can’t interpret.

Understanding the results

Now, let’s try to understand the results that were presented.

First of all, we should avoid recomputing the Names property over and over again. This is bad, especially when the property is getting data from a resource file.

However, the main reason why the benchmarks are not correct is because of LINQ and lazy evaluation.

Let’s take a closer look at the code:

// This reads all the names from the resources.

public List<string> Names => new Loops().Names;

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandClasses()

{

var classes = Names.Select(x => new PersonClass { Name = x });

for (var i = 0; i < classes.Count(); i++)

{

var x = classes.ElementAt(i).Name;

}

}

The classes variable is an IEnumerable<PersonClass>, which is essentially a query (or a promise, or a generator) that will produce new results each time we consume it. However, on each iteration, we call classes.Count(), which calls new Loops().Names that creates 1,000 PersonClass instances just to return the number of items we want to consume. When you do O(N) work on each iteration, the entire loop’s complexity becomes O(N^2), which is already quite bad. Then, on each iteration, we call classes.ElementAt(i), which probably needs to traverse the entire sequence from the begining again.

This means that the overall complexity is O(2*N^2) (which I know is still O(N^2)! And this O(2*N^2) time complexity and O(2*N^2) memory complexity. Meaning that for 1,000 elements, the benchmark could be doing millions of operations and allocating millions of instances of PersonClass` in the managed heap!

We can confirm this assumption by doing two things: 1) adding the MemoryDiagnoser attribute to see the allocations and 2) adding another case with either 100 or 10,000 elements to access the asymptotic complexity of the code.

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class ClassvsStruct

{

[Params(100, 1000)]

public int Count { get; set; }

public List<string> Names => new Loops(Count).Names;

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandClasses() {}

[Benchmark]

public void ThousandStructs() {}

}

And here are the results:

| Method | Count | Mean | Rank | Gen0 | Gen1 | Allocated |

|---------------- |------ |------------:|-----:|----------:|---------:|-----------:|

| ThousandStructs | 100 | 19.40 us | 1 | 0.6104 | - | 3.87 KB |

| ThousandClasses | 100 | 65.38 us | 2 | 39.5508 | 0.4883 | 242.93 KB |

| ThousandStructs | 1000 | 1,342.93 us | 3 | 5.8594 | - | 39.02 KB |

| ThousandClasses | 1000 | 4,844.48 us | 4 | 3835.9375 | 140.6250 | 23523.4 KB |

The results of this run are different from what was presented in the course, since my Loops().Names property is just a LINQ query. However, the same differences between structs and classes are still present: structs are significantly faster than classes. Why? Because of the allocations. Allocations in the managed heap are fast, but when you need to do millions of them just to iterate the loop, they would skew the results badly. You can clearly see a non-linear complexity here: the count goes from 100 to 1,000 (10x), and the duration goes up by a factor of 70 and the allocations goes up by a factorof 100.

It seems that the complexity is O(N^2) rather than O(2*N^2) as I expected. This is interesting! Obviously, my understanding of LINQ was incorrect.

Why? When I saw the results, my line of reasoning was the loop is O(N), Enumerable.Count() used in the loop is O(N), and Element.ElementAt(i) is O(N) as well. So for each loop iteration we iterate the loop from the begining twice.

I first checked the full framework sources:

public static TSource ElementAt<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, int index) {

if (source == null) throw Error.ArgumentNull("source");

IList<TSource> list = source as IList<TSource>;

if (list != null) return list[index];

if (index < 0) throw Error.ArgumentOutOfRange("index");

using (IEnumerator<TSource> e = source.GetEnumerator()) {

while (true) {

if (!e.MoveNext()) throw Error.ArgumentOutOfRange("index");

if (index == 0) return e.Current;

index--;

}

}

}

Hm… This is definitely O(N)!

But what about .NET Core version?

public static TSource ElementAt<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, int index)

{

if (source == null)

{

ThrowHelper.ThrowArgumentNullException(ExceptionArgument.source);

}

if (source is IPartition<TSource> partition)

{

TSource? element = partition.TryGetElementAt(index, out bool found);

if (found)

{

return element!;

}

}

else if (source is IList<TSource> list)

{

return list[index];

}

else if (TryGetElement(source, index, out TSource? element))

{

return element;

}

ThrowHelper.ThrowArgumentOutOfRangeException(ExceptionArgument.index);

return default;

}

The code is definitely different! There is a different handling of IList<TSource> and another case for IPartition<TSource>. What’s that? This is an optimization to avoid excessive work in some common scenarios, like the one we have here. We construct classes as a projection from List<T>, so the actual type of classes is SelectListIterator<TSource, TResult> that implements IPartition<TResult> and gets the i-th element without enumerating from the beginning every time.

Again, once we had a hypothesis, we can validate it. In this case, the simplest way to do that is to compare the number of allocations for the full framework and .NET Core versions using a profiler.

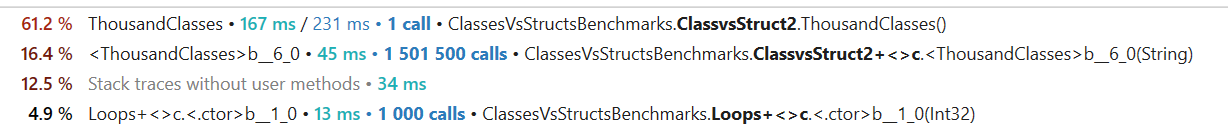

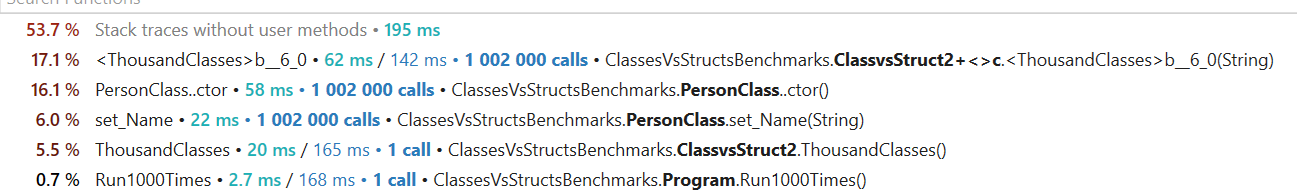

Full Framework results:

.NET Core results:

As you can see from the DotTrace output, the .NET Core version calls the PersonClass constructor 1 million times, and the Full Framework version calls it 1.5 million times. This makes sense since the asymptotic complexity is the worst case that does not always happen. ElementAt(i) has to iterate up to the i-th element and should go through the entire sequence only on the last iteration. But as you can see, the optimization that .NET Core has is quite significant.

Classes vs. Structs: Performance Comparison

Okay, we’ve analyzed and understood the data, but can I give advice on classes vs. structs? As I’ve mentioned already, this is a complicated topic, and I’m pretty sure benchmarking can’t provide any guidance here. The main difference between the two is the impact on allocations and garbage collection and how the instances are passed arounnd - by reference or via a copy. And its very hard to give an abstract advice on how and when this matters.

When I do a performance analysis, I start with a symptom: “low throughput” (compared to an expected one) or “high memory utilization” (again, compared to either a baseline or just “it looks way too high”). Then I take a few snapshots of the system in various states, run a profiler, or collect some other performance-related metrics. I do look into transient memory allocations to see if the system produces a lot of waste that could be an indication of a unnecessary work: allocating an iterator or a closure on a hot path could easily reduce the throughput of a highly loaded component by 2-3x. But if the allocations are happening infrequently, then I won’t even look there.

If I see GC-related performance issues, I would start looking into how I can optimize things. Using structs instead of classes is an option, but not always the first or the best one. Other options would be to see if we can avoid doing work by caching the results, or use some form of domain-specific optimizations. If I need to reduce allocations, I might switch to structs or try reducing the size of class instances by removing unused or rarely used fields.

Structs are definitely a good tool, but you really need to understand how to use them and when.

Key Takeaways

- Don’t trust the data you can’t interpret, especially the results of microbenchmarks. I’ve seen a ton of “best practices” based on stale or dubious microbenchmarking results.

- Understand the thing you’re measuring. Don’t make rushed decisions; dig deeper into the topic if you think you still have gaps in knowledge.

- Look behind the scenes. Understanding a few levels of abstraction deeper is crucial for performance analysis.

ElementAtis trickier than you might think, and overall, be VERY careful with LINQ in your benchmarks and in hot paths.